![]()

Photography Articles and Techniques

In Our Opinion

A Society of Images:

Constructing a Photographic Truth

By Robert Hirsch and Greg Erf

By Robert Hirsch and Greg ErfFrom Vol. 3 No. 4

Our daily existence is in flux as our society continually pushes the artistic, cultural, and scientific boundaries of what is humanly possible. In 1964 a human could run the 100-meter dash in 10.06 seconds. Today it is 9.78 seconds. In the future it could be 5.0 seconds. Experts argue about whether it is physically possible, but others say the human desire for transformation makes it only a matter of time before it happens. Photography parallels this evolutionary drive and the medium’s changing condition can make it hard to differentiate between truth and fiction.

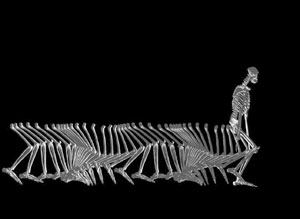

Visual representation of computer dynamic modeling techniques based on Lucy’s 3 million year old skeletal remains that provides more information as to whether Lucy’s limb proportions could support bipedalism. Credit—The Primate Evolution & Morphology Group and The University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. |

Time is a fundamental photographic concept that can be categorized into three basic structures that affect meaning: the past, the present, and the future. Generally, people find historical photographs easier to decipher because they can compare them with current societal thinking to attain an initial context for their meaning. Also, since the subject matter can be contrasted with similar topics from other eras, like the Civil War and the Vietnam War, people find these pictures often reveal something of significance to them.

Pictures involving the present are a part of daily life and therefore have familiarity that radiates a casual authenticity. Since they are so readily accepted they tend to reinforce what people already know or believe, including stereotypes. This can be dangerous because many people quickly draw conclusions based on faulty knowledge, such as “He has dark skin, a beard, and a turban so he might be a terrorist.”

The actual effects of contemporary pictures are not understood until we have the temporal distance to sort through them and eliminate the wheat from the chaff. Future images are concerned with the desire to push accepted boundaries of what is known, making their outcome difficult to predict and interpret. For instance, since May, three 35mm movie cameras have been aimed at ground zero in New York City from atop nearby buildings, each programmed to take a picture of the site every five minutes, 24 hours a day. They will all keep taking pictures, 288 per day, for at least the next seven years, the time that it is expected to take to rebuild the Word Trade Center site.

Star-Birth Clouds, M16, 7,000 light-years away, Hubble Telescope. Credit—Jeff Hester & Paul Scowen (Arizona State University) and NASA. |

Computer visualizations allow us to take concrete facts and project them backwards and forward in time to develop new theories about our past and our future. Consider Lucy, a set of prehistoric bones found in Ethiopia during 1973 with similarities to a modern human skeleton. By incorporating Lucy’s physical evidence into a visual software program scientists have formulated a model that suggests we might have walked more upright 3-1/2 million years ago. This new bipedal locomotion theory exemplifies how our need to explore can lead to new knowledge.

The core question remains, “Does this new information get us closer to the truth or does it add to the confusion about the actual gait of the earliest human-like species?” The Hubble telescope captures and returns images from deep space that look back in time. These digitally enhanced pictures have enabled astronomers to devise new hypotheses about the formation of the universe. Thus far, neither of these visual feats has changed any lives and may even lead some to believe that photography merely shifts the perception of truth to and fro. Time, and its inference of additional knowledge, will determine whether these visual observations impact the future or join the dustbin of failed theories.

In a world dominated by fantastic images, where the boundaries between fact and invention can be slippery, old concepts of photographic truth are no longer validated. This is not necessarily a bad thing. W. Eugene Smith set-up situations to be photographed and manipulated his prints in the darkroom, yet most people agree he produced outstanding humanistic pictures. Jerry Uelsmann uses a series of enlargers to create combination prints that reveal complex psychological perspectives about a subject. This brings up the issue of whether one way of working is more honest than another or is it a necessity to have multiple approaches that can convey the diversity of truths about any subject?

There are instances where viewers need to know the accuracy of the pictures since image manipulation by any means can alter how a situation is construed. Time magazine was criticized for racial stereotyping when the editors darkened O.J. Simpson’s police mug shot for their cover to make him appear blacker and therefore more criminal-like. Sophisticated technology has complicated the legal issues surrounding virtual

child pornography, which utilizes realistic computer generated images instead of actual children.

child pornography, which utilizes realistic computer generated images instead of actual children.While it is difficult to police pornographers, news agencies could establish guidelines for imagemakers that set clear definitions about how they portray reality. An informational image designed for public consummation could carry a symbol, such as an “@,” to indicate if it has been altered to help people better understand and decode such manipulated images. After all we do want to know if a new mark in the 100-meter dash was set using the same measurement of time and space as the previous record holders.

On-the-other hand, artists need to have the freedom to utilize a full range of working options to explore subjects without any stipulations. Here the emphasis should be on interpreting the content as opposed to how an image was created. Rarely is an artist asked what brush or brand of paint was used. Discussions about photographic art should steer away from f/stops and shutter speeds as this seldom leads to any fresh insight about what is being communicated. It is better to consider if selected moments of time have been integrated into a context of experience, meaning, and memory.

As the human brain filters through the ocean of images it provides one with a reading based on personal experiences. As people realize the intricacies that make up pictures, we may find it quaint that anyone once believed in an automatic, comprehensive photographic truth. The aspiration to push beyond the known limits makes it essential to revise the notion that a photograph is about outer appearances with a fixed meaning. This necessitates accepting photography as a living, evolving, and sophisticated interaction of data that objectively and expressionistically interweaves fact, fiction, science, and art into a visual construct.