![]()

In Our Opinion

When Something is Nothing and Nothing is Something

Robert Hirsch and Greg Erf

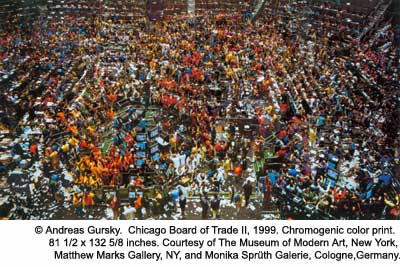

Robert Hirsch and Greg ErfLast spring the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York presented a major exhibition of photographs by Andreas Gursky that received high accolades. The son of a commercial photographer, Gursky’s super formalistic and hyper-detailed images fit the Stephen Shore mold cast by MOMA in the 1970s by its former photography curator John Szarkowski. The major difference is that today a computer was used to imitate reality, resulting in a picture that appears more real than reality.

Peter Galassi, MOMA’s current photography curator who trained under Szarkowski, declares Gursky’s large-scale hybrids as finally giving photography the quality to compete with painting (see: Andreas Gursky by Peter Galassi, Museum of Modern Art, distributed by Harry N. Abrams). Galassi continues the dialog by providing a prescription of what a photograph is supposed to look like (based on painting), by replacing the beautiful, full tone, black-and-white silver print with a seductive, canvas size, ink jet print with millions of colored dots. The computer and its accompanying technology have exchanged the handwork developed by Oscar Rejlander in the 1850s and perfected by Jerry Uelsmann in the 1960s.

What is the allure of perfect 7x16-foot prints that can hang in Fortune 500 boardrooms? Is it the glamour with a high technological price tag that furthers the physical disconnection between seeing/thinking and the making and output of an image at this scale? Or is it digital imaging ala Charlie McCarthy, a ventriloquist dummy with an ironic edge that mimics that which already exists?

What is the allure of perfect 7x16-foot prints that can hang in Fortune 500 boardrooms? Is it the glamour with a high technological price tag that furthers the physical disconnection between seeing/thinking and the making and output of an image at this scale? Or is it digital imaging ala Charlie McCarthy, a ventriloquist dummy with an ironic edge that mimics that which already exists?

Gursky’s premeditated olympian sized spectacles of color and pattern present subjects not as they are, but as we think they should be. The gigantic work continues the obsession that still haunts photography, the cult of detail, whose fundamental premise is that more information is good because clarity is the way we build our truths and it represents how we want to see the world. Gursky maintains the position that photography is best suited to be a cataloger of outward appearances because detail is emblematic of truth. Gursky’s teachers, Bernd and Hilla Becher, exemplify this Teutonic school of typological thought and are art world favorites because their work is predictable, saleable, and safe.

When first encountering Gursky’s work it can take your breath away with its sense of being new and important. Gursky’s pictures show us everything, but do they tell us anything? On extended viewing they become excessive, like a pizza with too many ingredients. They are too adroit, too colorful, have too much data, and too many people, which transforms them into objects of opulence and boredom.

Through the infinity of his crowd scenes individual identity is lost, people metamorphose into insects, making them unknowable. Their titanic size shouts, “stand-back and look at me, but don’t get too close.” Intimacy is not encouraged. Often there is so much going on that fatigue and weariness sets in and the everythingness of the compositions turns into nothingness. In a culture of now these beautiful giants issue artistic license for the production of boring pictures. After the immediate wow wears off viewers can be left with the sensation of “so what,” converting these excessive colossals into cold-blooded masterpieces of indifference.

Gursky represents Szarkowski’s formula dressed in new clothes. It is indicative of MOMA’s photography department’s on going inability to recognize and present important aspects of contemporary practice, preferring to concentrate on harmless, orderly illusions of seamless reality that distances them from the diverse and multi-dimensional imagery of today. Rather than reform this stale vision, MOMA has passed the buck by forging a relationship with the contemporary arts center P.S. 1 in Long Island City to handle this aspect of contemporary arts. Visit a not-for-profit photography center, such as CEPA Gallery (www.cepagallery.com) to see work that reflects today’s challenging vision and artistic values.

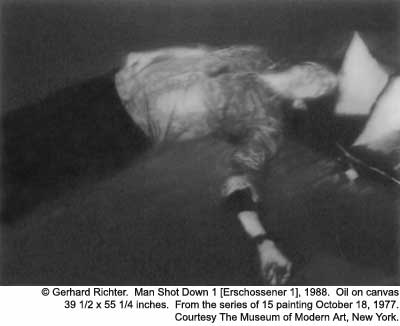

In contrast, this spring MOMA presented the photo-based work of Gerhard Richter, an artist who developed in both East and West Germany (see Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting by Robert Shorr, Museum of Modern Art, distributed by D.A.P.). Seeing the show in New York after 9/11 one can admire how Richter merges painting and photography to refashion history (his father was a member of the Nazi party and he a member of the Hitler Jugend). The prime example of the work’s political nature can be seen in the controversial series October 18, 1977, which deals with the radical Baader-Meinhof terrorists who died in jail. The official cause was suicide, but others claim they were murdered.

In contrast, this spring MOMA presented the photo-based work of Gerhard Richter, an artist who developed in both East and West Germany (see Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting by Robert Shorr, Museum of Modern Art, distributed by D.A.P.). Seeing the show in New York after 9/11 one can admire how Richter merges painting and photography to refashion history (his father was a member of the Nazi party and he a member of the Hitler Jugend). The prime example of the work’s political nature can be seen in the controversial series October 18, 1977, which deals with the radical Baader-Meinhof terrorists who died in jail. The official cause was suicide, but others claim they were murdered.

These subdued and brooding images powerfully negotiate the boundaries between abstraction and representation, not through the algorithms of a machine but through the human quirks of mind and hand operations. The work looks photographic, but violates the traditional tenets of the medium. They are blurry, gray, muddy, and out-of-focus, yet these re-interpretations of photographic reality hit deep and hard at the nightmare of history. The blur conveys a flowing sense of sadness and remembrance, something that cannot be held onto. Here the syntax of photography and painting meet to emotionally show us the disturbing, death worshiping ghouls of failed ideologies that continue to resurrect themselves.

These small, black-and-white images provide no solid ground, but like the sirens that lured Ulysses, their enigmatic nature calls one back over and over again. Richter states, “I steer clear of definitions.” These refusals to do the expected, to offer pat answers, or a smiley face provides the work with intrigue. It is precisely Richter’s ability to display this combination of uncertainty that provides a tension of boundless and unsettling possibilities that are simultaneously about something and nothing. There pseudo-narrations place the murkiness of life right before our eyes. They deal with death and time yet their vague dream-like qualities makes them fine memorials that can transform themselves into anything viewers want them to be.

In a crowded and noisy world Richter’s monochrome images offer the luxurious room for silent contemplation. In an ugly world that has declared war on beauty, these inscrutable surfaces increase the sense of aesthetic pleasure that braces itself against despairing fragments of loss and ruin. In a commercial world they are decidedly poetic in character. In a world of sound bites and theories they do not tell you what to believe or think. There are no bright flashy messages and even the high-quality reproduction fails to provide an accurate sense of their powers. In a world of stand-in reproductions they demand to be seen and studied in person. Such authentic ambiguity acknowledges the lack of any traditional deity and its accompanying dogma is in favor of the experimentation of self-discovery. Ultimately Richter’s work tells us that good picturemaking is more than representation and challenging art can drive us beyond our reflected world notions.

•Hirsch and Erf are participating in a traveling exhibition, The Culture of Landscape, which explores the dichotomies, myths, and symbols of our cultural and natural environment. For details and booking information visit: www.negativepositive.com.