![]()

The View From Here

Along about April

By Margaret Regan

By Margaret ReganAlong about April, we started hearing again about Rodney King.

On the 10th anniversary of the Los Angeles riots, newspapers once again recounted the mayhem that erupted after white police officers were acquitted in the black man’s infamous videotaped beating. Distraught over the violence, King made his famous plea: “Can’t we all just get along?”

The answer still is no, apparently not. At the end of a grisly year in which the world has grown more murderous by the day, even the art world is racked by divisions, less deadly certainly, but nonetheless heartfelt. Classicists don’t get along with multiculturalists, and lovers of pure form can’t abide artists who promiscuously jump media boundaries. The new category of “contemporary art” angers purists of all stripes by positing nearly every material as a legitimate art medium. Painter Julian Schnabel of New York glues broken crockery to his canvases. New Mexico’s Harmony Hammond has a whole series of paintings made of oil on canvas, and linoleum ripped up from the kitchen floor. In my dozen years of reviewing art, I’ve seen everything from a sculptural pair of underpants studded with a thousand straight pins, to airy mobiles made of pig gut wafting in a gallery breeze.

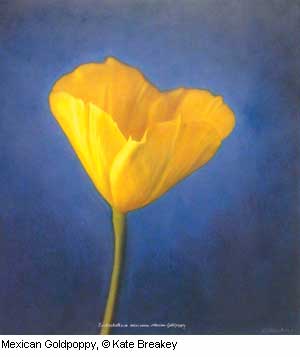

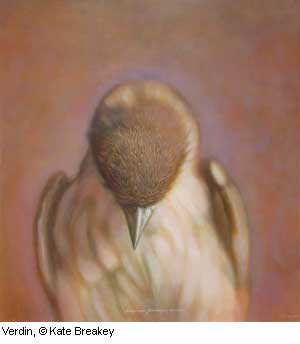

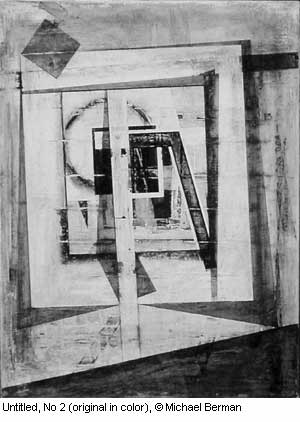

The answer still is no, apparently not. At the end of a grisly year in which the world has grown more murderous by the day, even the art world is racked by divisions, less deadly certainly, but nonetheless heartfelt. Classicists don’t get along with multiculturalists, and lovers of pure form can’t abide artists who promiscuously jump media boundaries. The new category of “contemporary art” angers purists of all stripes by positing nearly every material as a legitimate art medium. Painter Julian Schnabel of New York glues broken crockery to his canvases. New Mexico’s Harmony Hammond has a whole series of paintings made of oil on canvas, and linoleum ripped up from the kitchen floor. In my dozen years of reviewing art, I’ve seen everything from a sculptural pair of underpants studded with a thousand straight pins, to airy mobiles made of pig gut wafting in a gallery breeze.The same art revolution has long since sundered photography into warring camps. If “photograph” literally means “light writing,” photography has become the text for a dizzying variety of new scripts. To the dismay of proponents of the pure print, photographs nowadays get painted, scratched, burned and sliced. They end up in collages, installations and sculptures, and not always in starring roles. Kate Breakey, an Australian transplanted to the American Southwest, colors her giant photographs of animals and birds with oils and Prismacolor pencils. New Mexican Michael Berman fashions intricate montages and installations that combine drawing and painting with photographs he’s shattered into shards.

In the midst of all this mixed-media ferment, the photography world is celebrating the 100th birthday of the late Ansel Adams, master of aesthetic austerity and high priest of the sacred print. It’s hard to imagine images more beautiful than Adams’ snow-dressed Yosemite oak or his cascading sand dunes at Death Valley National Park.

But does that mean that Adams is where photographic exploration begins and ends? Of course not. Adams himself and the other idealistic founders of the f/64 group, including Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston, certainly argued for “pure photography.” In a 1932 manifesto, they declared: “The Group will show no work at any time that does not conform to its standards of pure photography. Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form.”

But does that mean that Adams is where photographic exploration begins and ends? Of course not. Adams himself and the other idealistic founders of the f/64 group, including Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston, certainly argued for “pure photography.” In a 1932 manifesto, they declared: “The Group will show no work at any time that does not conform to its standards of pure photography. Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form.”These young photographers were rebels with a cause, rising up against pictorialism, a dreamy style too close to painting for comfort. They took the revolutionary position that photography should be itself, a new and distinctive art form. But in one of those ironies that life regularly yields, admiration for their groundbreaking achievements can fossilize into a conservative adherence to art of the past. Modernists can metamorphose into reactionary cranks intent on squelching innovation.

Kate Breakey, the Australian artist who has achieved considerable success with her painted and penciled photographs, is one artist who has been stung by their venom.

“I do get grief,” Breakey says. “I’ve had a couple of reviews that said what I did to the photograph is absolutely sinful. The purists don’t like it. To them, the print is a sacred thing, not to be bent, or colored.”

For her, the mixing of the media in her works is a happy amalgam of two delicious genres. As an undergrad at the South Australian School of Art, Breakey studied both painting and printmaking before switching to photography. And at the University of Texas, Austin, she got a master’s in photography.

“I love photography but I couldn’t give up using paint and inks,” she says. “I love the smell of it. I love everything about it. My work now is a way of marrying the two.”

“I love photography but I couldn’t give up using paint and inks,” she says. “I love the smell of it. I love everything about it. My work now is a way of marrying the two.”She sees this mixed marriage as a co-mingling of the virtues of both media.

“Photography is fairly objective,” she says. “It’s about the physics of light, something that has to have existed in real life. It has a strong objectivity. When you start painting on top, you’re entering the subjective.” But Breakey is conscientious about the biological record; she keeps her colors faithful to nature, but “more vibrant, over the top.”

Different as their work is, Breakey shares a love of nature with Adams. Like him, she begins her art by going out into the wilderness. Living now at the edge of the Sonoran Desert in southern Arizona, Breakey rides her horse into Saguaro National Park, in search of the critter corpses she memorializes in her pictures. The artist says that even as a small child on the family farm near Ade-laide, Australia, she couldn’t bear the deaths of fled-gling birds who’d tumbled from the nest or of ducklings too weak to live.

“Nature massacres things in large numbers and just carries on,” Breakey says. “It’s kinda sad, all those little things that die.”

Nowadays, many of the dying critters not fortunate enough to be saved by Breakey’s ministrations (“I’m a great resurrecter but it’s often a lost cause.”) end up memorialized in her pictures. Now 150 images strong, her Small Deaths series consists of larger-than-life photographic close-ups of dead animals and flowers, hand-painted in luminous colors. They’re desert creatures late of Texas and Arizona, graying lizards, a pair of Gambel’s quails, male and female, a ruby-throated hummingbird, a Mexican evening primrose.

Breakey makes gigantic portraits of just the head and torso. Blown up to 32 by 32 inches, the creatures are roughly human-sized. She paints the toned gelatin silver prints with transparent oils, and finishes them off with Prismacolor pencil, making delicate strokes for feathers and scales and eyelids. As an artist, she forces viewers to confront each creature as an individual, “each with a unique life story, a different tragic death.” The work powerfully links us to nature’s cycles of life and death.

Her critics might be surprised to learn that Breakey covers a lot of art historical ground in Small Deaths. Contemporary as they are, with their mixing of media and their stark figures floating on abstracted space, the pictures nevertheless have a 19th century air. Like Breakey, early photographers would create mementos mori, memories of the dead, but instead of animals they immortalized dead children, producing photographs of grieving parents holding the corpse of a dead child. And before the days of color photography, commercial studio photographers would gladly paint in colors the image of a dead child, or a dead grandmother.

Michael Berman’s photo montages are more abstracted than Breakey’s work but like her he alters the technically produced photograph with the touch of the human hand. Thematically, though, his work is closer to Adams’ art of the sublime landscape. Berman starts by walking into the western wilderness, or what’s left of it since Adams’ early ecstatic explorations of places like Yosemite. He photographs monuments and canyons and—purists take note—prints them up first in small editions. But here he deviates from the Adams path. As he puts it, “these same negatives and photographs are then collaged in mixed-media paintings or works on paper… the images are often fragmented, cut up and reassembled, and subsumed in multiple layers.”

Michael Berman’s photo montages are more abstracted than Breakey’s work but like her he alters the technically produced photograph with the touch of the human hand. Thematically, though, his work is closer to Adams’ art of the sublime landscape. Berman starts by walking into the western wilderness, or what’s left of it since Adams’ early ecstatic explorations of places like Yosemite. He photographs monuments and canyons and—purists take note—prints them up first in small editions. But here he deviates from the Adams path. As he puts it, “these same negatives and photographs are then collaged in mixed-media paintings or works on paper… the images are often fragmented, cut up and reassembled, and subsumed in multiple layers.”The fragments are lovely, and haunting. It’s tempting to read an environmental message into this aesthetic destruction: just as surely as Berman is breaking down his prints, human encroachment is breaking down the western landscape. And here’s where he and Ansel, a fervent conservationist, as environmentalists were called in the old days, could agree. Both of them, wrote art critic Nancy Spector, had “a faith in the spiritual essence of the yet unsullied landscape.” Recording and lionizing and calling attention to that landscape was Adams’ life work. It’s Berman’s as well.

Surely even Adams would not have pushed for an All-Ansel-All-the-Time format for his artistic descendants. There will always be a place for beautifully classic black-and-white photography, but there’s got to be room as well for experiments in crockery and paint and, yes, even pig gut. These may not evolve into enduring masterpieces, but without innovation art dies. After all, even Adams sometimes put his photographs into standing screens that today would be called installation art. And his own working method shows that over time he fiddled with his lights and darks.

Perhaps the best that can be hoped for is that cutting edge artists and purist critics can agree to disagree. Maybe then they really could all just get along.

Kate Breakey’s work can be seen in her monograph Small Deaths: Photographs by Kate Breakey. Intro-duction by A.D. Coleman, University of Texas Press, Austin, 2001.

- Margaret Regan is an award-winning journalist who has covered the arts for a dozen years. Her work has appeared in New York’s Newsday, in Make: A Journal of Women’s Art in London, Camera Austria, and numerous publications in the U.S.