| Photography

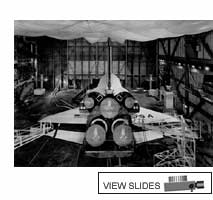

Articles and Techniques A Conversation With John Sexton  INTERVIEW BY INTERVIEW BYTHOMAS HARROP For over 27 years, John Sexton has devoted himself to the study and advancement of photography. While pursuing a course of study that placed him squarely on track for a career in commercial or in-dustrial photography, Sexton had a life-changing experience. In the early 1970s, he attended a session of the Ansel Adams Yosem-ite Workshops. During his studies, there he was exposed to people who were passionate about doing photography as a personal state-ment, not just as an assignment-based career. In 1975, Sexton was invited back to the Ansel Adams Workshops as an assistant. Sexton’s job was to clean the floors and work in other menial capacities. Still, he continued to be drawn to the energy and mas-tery of the dedicated photographers he found at the workshops. Three years later, Sexton got the call the set him squarely on the path that his life would follow. Ansel’s assistant at the time, Alan Ross, was moved up to instructor for the workshops and this left open a position as Ansel’s personal as-sistant during the workshops. A year later, when Ross left to work in San Francisco, Adams asked John to move up from Southern California to work with him full-time. As pho-tographic and technical assistant to Adams, Sexton conducted the tests used for Adams’ books The Print and The Negative. For three and a half years, Sexton continued to work full-time as Ansel’s assistant, and then, in 1982, he decided the time had come to pursue his own photography.  Since setting out on his own career, Sexton has proved himself in the area of fine-art large format photography. In addition to conducting a plethora of popular workshops each year, Sex-ton has produced several books of his own work. Since setting out on his own career, Sexton has proved himself in the area of fine-art large format photography. In addition to conducting a plethora of popular workshops each year, Sex-ton has produced several books of his own work.His first two books, Quiet Light and Listen to the Trees, achieved great crit-ical and popular success and his latest outing, Places of Power: The Aesthetics of Technology, promises to expand his reputation even further. Although some will see this new book as a departure, it is firmly rooted in the West Coast tradition of beautifully crafted black-and-white photography. Recently, Photovision Editorial Director Thomas Harrop had the op-portunity to speak with Sexton about his new book, the state of photography and a great many other things both pho-tographic and philosophical. Thom Harrop: What keeps you excited about photography and interested in your work? John Sexton: Brett Weston used to say that photography is 90% sheer bru-tal drudgery and 10% inspiration. I tell my workshop students it’s that 10% that keeps us coming back. I see myself as a professional, and my definition of a professional is that you have to do a good job even on a bad day. You want your doctor to be professional [laughs]. You don’t want to see their work suffer just because they’re having problems with their family. I think it is the same thing with photog-raphy. There are some days I don’t want to go in the darkroom to make a print to fulfill a commitment. I would much rather go in and play with a brand new negative, but I can’t because I have to honor my commitments.  But on those occasions when I look at the ground glass, or turn on the white lights while anxiously holding a piece of film, or look at a freshly squeegeed print, that’s the exciement that keeps me going. TH:Where have you been photo-graphing recently? JS: In May I was in the Southwest and, after a workshop, I spent ten days making the last of the pictures for the book, Places of Power. I made two during that trip that ended up in the book. Before that, I made four others in late March when I went to the Kennedy Space Center most recently. Each time I get out to photo-graph it generally follows a period of idle time. If I’m teaching work-shops and I go out and do a demo on the view camera or the Zone System, that kind of gets me back in to practice, but there’s nothing like really getting out and photo-graphing on a regular basis. It usually takes a few days to get back into the swing of things. You know, you put the wrong lens on the camera, or you kick the tripod leg, or you forget to close the shutter and pull the dark slide; things that once you’re in practice you would hardly ever do. It takes a few days to get the cobwebs out and really get to the point where you are functioning efficiently and the creative juices begin to flow. TH: What inspires you most?  JS: Well, for the last few years it has been ancient Anasazi sites in the Southwest. They are probably the most challenging subject and the one with which I have the worst batting average. I look forward to going to An-derson Ranch where I have the luxury of teaching a two-week long workshop. That workshop also gives me the opportunity to have a weekend to play, and my idea of playing will be photographing. Then bringing the negatives home, souping the film and trying to find the time to make prints. Time, I think, is the biggest “enemy” of most people’s lives. TH: Do you edit your own negatives, or do you have someone go through them with you when you get back? JS: My girlfriend, Anne Larsen, is an excellent photographer. We look at each other’s work and comment on it objectively. Sometimes I have something I’m really excited about and she’ll say, “Well, that’s not re-ally working.” Generally she’s right because she offers a greater level of objectivity. Once you’re invested in the making of an image you lose objectivity. I soup all my own film, and Anne and I help each other with contact sheets. It’s fun to see that first step in getting the negative onto paper, to study the proofs and figure out which ones I want to do first. Very often I have favorites. There will be two or three that felt like they were the most exciting and they’re sometimes the biggest disappointments. And there are the ones where you say, “Oh, yes! I got it!” I put a loupe on those right away and make sure they’re sharp. It’s distressing when I botch-up somehow. Maybe there’s a cable release hanging down in the middle of the picture. TH: What kind of equipment do you use? Anything other than 4x5?  JS: For 99.9% of my work I use a 4x5 view camera. When I was first forced to use a 4x5 as a photography major in college I hated it! I thought it was a really inefficient format. It was very inconvenient and awkward, and I didn’t like that upside-down and reversed image. I just wanted to get through the classes where I had to use it and go back to my Hasselblad. JS: For 99.9% of my work I use a 4x5 view camera. When I was first forced to use a 4x5 as a photography major in college I hated it! I thought it was a really inefficient format. It was very inconvenient and awkward, and I didn’t like that upside-down and reversed image. I just wanted to get through the classes where I had to use it and go back to my Hasselblad.Somewhere along the line I got used to it. Now it’s the format I feel most comfortable with. I also have an 8x10 and a 5x7. I’ve owned 21&Mac218;4 cameras and I like them for certain things. I also own a 35mm, but the last time it was off the copy stand was years ago. The one exception to this has been some 21&Mac218;4 work I have recently done at the Kennedy Space Cen-ter with the Hasselblad ArcBody. I have used it for landscapes as well, but it seems to be most productive for me in shuttle photography. I start a long exposure with my 4x5 and then, because I get to use much wider apertures with the Hassel-blad, I can get two exposures off with the 21&Mac218;4 while I’m making an 8 or 10 minute exposure with the 4x5. I use the 35mm and the 45mm lenses and at f/11, everything in the world is in focus! There are a couple of images of the Shuttle that would have been impossible with the 4x5 because of limited time or cramped space. That being said, I just love my 4x5. It’s the camera that feels the most comfortable to me. I’ve used the Linhof Technika for 20 years. I bought my first Linhof used for $400 in 1980. I stripped it down and got rid of the rangefinder, which is just not a part of the way I use the camera. I was trying to get rid of weight and bulk. Four or five years later I sold it to a friend, who still uses it, then I bought a new Linhof in Germany. I traded that one in about three years ago and bought an updated model which I currently use. When I’m in the landscape that’s the camera I use, and when I’m doing industrial subjects, like the Space Shuttle, I use the Linhof Technikardan which is a folding monorail camera. It’s really great with super wide angle lenses. The lensboards on the two cameras are interchangeable which is very convenient. TH: Do you prefer any specific lenses or do you use whatever is appro-priate?  JS: Whatever is appropriate. Then if it doesn’t turn out right I just say, well, I didn’t have the right lens. [laughs] For seven years, from 1973 to 1980, I only owned one lens. That was, as I like to say, “the best decision I never made.” There wasn’t anything in the wal-let to buy a second lens. That was a used 210mm Schneider Sym-mar lens and today that’s the focal length I use most often. JS: Whatever is appropriate. Then if it doesn’t turn out right I just say, well, I didn’t have the right lens. [laughs] For seven years, from 1973 to 1980, I only owned one lens. That was, as I like to say, “the best decision I never made.” There wasn’t anything in the wal-let to buy a second lens. That was a used 210mm Schneider Sym-mar lens and today that’s the focal length I use most often.In 1980, I bought a Nikkor 120mm, 210mm and 300mm. So I tripled my lens selection. If you look in the back of Quiet Light or Listen to the Trees, where pictures span a fair amount of time, you’ll see the 210mm there a lot, and every once in a while a 90mm. That’s a lens I borrowed as a stu-dent, and later as an instructor, from school. TH: Was that a 90mm Super An-gulon? JS: Yes. But today I use primarily Nik-kor lenses, except for a 58mm Schneider, which is a superb lens, and a 450mm Fujinon which I’ve had since about 1983. I now use a little tiny 200mm f/8 Nikkor which is a phenomenal lens. I can fold my Linhof with the lens in place, it’s that small. I didn’t use all the coverage the big 210mm had, and the extra ten millimeters of focal length is meaningless. You can’t see the difference. I tested the Nikkor before I bought it because I thought maybe it’s not as good as the larger 210s, but I went out and did side-by-side pictures, then made 16x20" prints. They looked great. I must say though, that my Schneider 58mm is a super piece of glass. When I’m working on the Space Shuttle that’s the lens I use quite often. Almost everything on the Space Shuttle requires a wide angle lens because I’m usually either very close to the orbiter or inside the orbiter — it’s very, very cramped quarters. With the 58mm I am often backed up against a bulk-head or other obastacle. Even with the Anasazi sites I often use wide lenses to exaggerate the scale of the objects which are pretty small. Industrial subjects are just made for wide lenses, especially when you are doing interiors. TH: What film and paper do you cur-rently use? JS: For years I only used Tri-X. For the last 14 or 15 years, since a little before it was introduced (be-cause I was one of the people who consulted with Kodak on T-MAX films) I’ve used T-MAX 100. Oc-casionally, in low light situations or in the case of a landscape when wind might cause camera move-ment, I use T-MAX 400. I’d say 70 to 80% of what I do is T-MAX 100. Some people have trouble controlling that film. Based on the good advice of the instructors I had at Cypress College, we were taught to process film very accurately and one of the classes we took was color film processing. We had to learn how to process color transpar-encies and negatives. Twice during the semester each student had to process the whole film run for the class. So those people who weren’t getting it as quickly as others got a lot of help from everybody to make damn sure they were “with it” when it was their turn to process. I remember the importance of timing and temperature being im-pressed upon us. I said to myself, “Hey, if it matters for color, it prob-ably matters for black-and-white.” So I tried, in my home darkroom with the controls I had available, which weren’t particularly sophis-ticated — ice cubes, hot water, and stuff like that — I tried to control my black-and-white.  When T-MAX came along and it was a process sensitive film, to me it wasn’t really an issue because I had already, for several years, tried to keep my process under control. If it’s eight minutes, I wasn’t doing it 7:45 or 8:15. I mean, how hard is it to do it eight minutes? For years (when I was manually processing) I always put the ther-mometer in the tray of developer once I got into the stop, and then the first thing I looked at when I turned on the white lights was to see if my temperature drifted. I had arrived at methods to try and keep that temperature plus or minus a degree. And if it wasn’t, I thought I’d done something wrong. Today my JOBO processor and Expert film drums handle the consistncy better than I ever could. I’ve used T-MAX 100 for a long time and it works very well for me. I know it’s ins and outs. I’ve made a lot of good negatives with it and in the process of learning it, I’ve made a number of bad negatives. It just takes practice to learn a material. I print everything on fiber-based paper. There’s nothing wrong with resin coated paper, but it’s my de-sire to make sure that black-and-white fiber-based paper is available for as long as possible. So I’m going to spend every dollar on material that I want to use. I don’t think there’s a sheet of resin coated paper in my darkroom. I’ve used it over the years and it’s much better than it used to be, but the only way I can tell the manufacturer, whether it’s Kodak or Ilford or Agfa, that this stuff is important to me is to vote with my dollars. I have been using a lot of Kodak POLYMAX Fine Art over the last few years. I also use some Agfa In-signia paper, a little Forté Warm-tone and Oriental Seagull. Those are pretty much the four papers that I work with regularly. That’s plenty for me. That’s a lot to juggle at one time. I have used thousands of sheets of these papers over the years, learning the idiosyncrasies of each. It takes a long time. A lot of people just move on to the next negative after two or three sheets if they don’t have the print they want. Sometimes, that’s the right answer. I’ve printed a box of paper and then later realized that there was nothing in the picture to begin with. It was just a foolish attachment on my part. On other occasions I have “discovered” the print I wanted only after many sheets of paper, and many hours have been invested in a negative. TH: I think that happens a lot. You’re involved in some sort of experience that’s really special and you want it to convey that feeling, and some-times it’s just not there. JS: I like to tell people, jokingly, at workshops that the ultimate pho-tographic bit of knowledge is just a few words: “I wanted it that way.” Because if somebody asks why is a picture this way, or why did you do that, you can always say, “I wanted it that way.” I always add that if you have to explain too often that, “I wanted it that way,” either there’s something missing in the picture or you ought to want it another way. You don’t want people always asking you why it’s out of focus or why it’s too dark. Sometimes we have this attachment to the image and a viewer with objectivity can cut right to the core and ask, “why is 90% of this picture irrelevant.” When we are successful and make a picture that is exciting to others it’s not based just on shutter speeds and f/stops and what sort of tricks you can pull in the dark-room. It’s taking your experience and translating it in a way that is magical.  TH: I was wondering if you could share some of your impressions of Ansel Adams. What was he like and how did you come to be his assistant? TH: I was wondering if you could share some of your impressions of Ansel Adams. What was he like and how did you come to be his assistant?JS: Ansel was a down-to-earth guy. He loved to be around photographers and he found it stimulating to be around people who loved photog-raphy and other creative outlets musicians, painters, etc.— any thoughtful people. I met Ansel in 1973 when I was a student at a two-week-long workshop in Yosemite. At that time I was a photography major in college. My desire was to go to work as an industrial or advertising photographer, maybe in a corporate environment, or an aerospace company — something like that. But when I went to Ansel’s workshop, I gained a feeling, not just from Ansel but also the other dedicated individuals that he had on his faculty, that they all truly loved photography. They pursued it with great professionalism but they obviously were in love with the process and the magic that ex-ists within it. It was at that workshop that I decided I wanted to really try and learn to do black- and-white the way I saw Ansel and others on the staff doing black-and-white. The prints were amazing. It was also then that I decided that I wanted to try and somehow figure out a way to do photography for myself rather than for others on commercial as-signment. That workshop, without a doubt, changed my photographic life. A year later I went back as an assistant at an Ansel Adams Gallery workshop. I applied for it and was accepted. My job was literally cleaning the darkroom floors and stuff like that. Ansel was not teaching at that work-shop; Phil Hyde was one of the instructors. It was actually a color workshop. But I would do anything just to get back into the workshop experience. I also signed up as a student for a workshop with Paul Caponigro and Wynn Bullock and a number of other people. In 1975, I got to go back as an assistant at Ansel’s workshop. I think in ’75 they started doing two each year, back-to-back, and I did both of them. I didn’t miss an Ansel Adams workshop as either Ansel’s assistant, a director or an instructor until they stopped do-ing them, and that was after Ansel died. As far as I know there are only two people who have been to more Ansel Adams workshops than me: Ansel and Virginia Adams. Being an assistant, I began to have communication with Ansel on a more regular basis. I would go visit his home every six months with a new box of prints, and make an appointment to show Ansel my photographs. He would comment on them and offer suggestions of ways to improve them, then I’d go back home and work on those prints and make new negatives. Anyway, in 1978, Alan Ross, an excellent photographer, was Ansel’s assistant and he was moving up to be an instructor at the workshops. So, Ansel needed someone to work closely with him, just during the workshop, and he asked me if I wanted to do that, and I said, sure. That was a great experience. The following year, Alan moved to San Francisco to open a studio and Ansel asked me to move from Southern California and work for him. At that point, he was just be-ginning to work on the books, The Negative and The Print … well, The Negative, actually ... The Print followed … and he asked me if I would conduct all the tests for those books. I worked there full-time until late 1982, and then from that point on I decided to do my own pho-tography. When I went to work for Ansel, he said, “We’ll both know when it’s time for you to move on; you can’t be my assistant forever. You can’t be anyone’s assistant forever.” Ansel demanded a lot of those around him, but he didn’t demand any more than he demanded of himself. And we had a lot of fun. He had a great sense of humor. That’s the one thing that books and videos fail at conveying ef-fectively. I think a sense of humor, unless you’re live and in person, is very difficult to convey. He was a very funny and brilliant person who used his sense of humor as a release and relief from the intensity with which he approached his projects. One of the most memorable occurrences took place sometime around 1981. Ansel had been in the darkroom working on a neg-ative he had made nearly 50 years earlier. He had printed it many times previously and reproduced it in a variety of books. He was working on a set of prints called The Museum Set, and, of course, he printed all his own negatives for exhibition prints. Anyway, he was struggling with this negative and he’d been out to the cupboard for two or three different kinds of paper. I don’t remember how many hours he worked on it, it might have even been the second day, he came out and said, “I finally got the print I wanted when I made the negative.” The negative had been made in 1932! Ansel was beaming! That excitement, that inspi-ration, meant so much to me because here’s somebody who is at a point in his life, roughly 80 years of age, doing photography for many years, and he still found the excitement when the creative struggle led to a satisfying experi-ence. I still look back on that day as an important day in my life. He was so excited by that print, which he really struggled with. In his mind it was the best print he had ever made of that negative. I really felt reaffirmed that photography was something that could be a lasting and rewarding experience. And I don’t think it’s just photography. I think it is the entire creative process. It’s being involved in something that is ex-citing to you. I remember the magic I found in the darkroom when I first saw a print made. It’s not like every sheet of paper is magic anymore, but when you get one that you re-ally want, it truly is magic. I have a pretty good idea, of how the whole thing works, but I still can’t quite comprehend how it all works. The fact that one can work in the darkroom, then turn on the lights and there’s this picture in front of you, is still pretty amazing to me. Somehow it’s far more amazing than waiting for an inkjet print to churn out the other end of the ma-chine or watching that little wrist-watch icon in Photoshop. I mean, they’re great tools, don’t get me wrong, but there’s just something about being in the darkroom that’s a more personal and sensual expe-rience for me. TH: Let’s talk about Places of Power. How does one go about dialing up NASA and saying, “Hi, I was wondering if I could have complete access to the Space Shuttle inside and out?” How did you get the whole thing going and who was that first call to? JS: Well, the first calls were naively directed to the wrong people. I first got the idea to photograph the Space Shuttle in March of 1990 driving home from the first day of photographing Hoover Dam. I was sitting at a traffic signal and asking myself why I was photographing ancient Anasazi sites, power plants, and now Hoover Dam. That’s when I understood that I was examining the aesthetics of technology through time. I decided the Space Shuttle would be perfect to represent today’s technology. I unexpectedly started photo-graphing power plants in 1987 when I was looking for a field trip location for a workshop. I wanted to challenge the students aesthetically and technically. One of the individuals in the work-shop was the general manager of a power company. I had seen one 8x10 print of his the year before, of the inside of this power plant, and it was really great. So, when I arrived in Wisconsin to scout for this workshop location I called him and said I remembered that picture. I wanted to come see about the possibility of bringing the class to the power plant. Fortunately, he said that it was a good idea. When I walked in there I thought, “This is amazing! I’ve never seen anything like this before.” I didn’t really want to photograph the power plant even though it looked so beautiful. At the same time it had this kind of antithetical aspect to what I thought my photography of the landscape was about. But I did make photographs and I kept going back and photographing the power plants at this power cooperative for myself. In 1990, I had to got to PMA in Las Vegas to sign posters along with other photographers for Nikon. They gave us all a day off and I thought, what am I going to do on my day off? I could go out to Valley of Fire, I could go to Red Rock Canyon, then I thought, geez, I bet there’s some really neat stuff at Hoover Dam. I’d never been inside Hoover Dam, so I contacted them and sent them some power plant pictures. They said I could come and look around and take what they call a “nooks and crannies tour.” It was amazing! I photo-graphed all day and into the night. As I was driving back to my hotel in Las Vegas I was thinking, “Wowee, what a great day of photography! Why is it so great? Why am I mak-ing these pictures now?” I realized that the thread of con-tinuity in my mind was that these were all things that were built, crafted and engineered by human beings, and they also extended a thousand years in time. I now needed something that was futuristic, and it was at this traffic light that I got the idea to photograph the Space Shuttle. I made my first exposure three years later. I spent a fair amount of time and energy trying to figure out how to get permission. It was difficult to explain to NASA what I wanted to do. I wanted to reveal the asthetic beauty I hoped I would find in the Space Shuttle, but I had never acturally seen a Space Shuttle, let alone photographed one. I was try-ing to explain that I wanted to pho-tograph the Shuttle in a way I had not seen it photographed before: as a piece of functional sculpture and artwork. It was difficult to try and explain what I wanted. All I had was images in my mind. A lot of those images evaporated very quickly, when I first visited Kennedy Space Center because I thought I would find this spacecraft just sitting in an open hangar, if it wasn’t out on the launch pad. Well, I found out that it was completely encumbered in apparatus. When I first entered what I now know is an orbiter processing fa-cility, I finally met my first Space Shuttle. I was really nervous that I wouldn’t have a reaction … that it would just be a “bucket of bolts.” All of a sudden I looked up and I saw the distinctive mosaic pat-tern of the tiles. I realized that I was standing right underneath the orbiter Endeavor. I could feel my heart start to pound, and I knew in that instant that my photographic project was valid; that there were pictures to be made. I made my first picture, which happens to be in the book — a pho-tograph of landing gear. And then I think I did a tile detail that’s in the book as well. So, that was in March. I came back a few weeks later to try and photograph a launch, but I didn’t even get to see the launch; it was aborted. My objective was never to get a launch picture. I’ve tried twice, and I did get to see one launch, which was most memorable and impres-sive, but I have zero launch pic-tures. I wanted to just photograph the pure aesthetic of the shuttle. Seeing the launch, however, gave me an entirely new respect for the power and complexity of the entire Space Shuttle system. On my second visit to the Ken-nedy Space Center, there were two people from NASA in an office looking at the pictures and the one fellow says, “He really is photographing the Shuttle in a dif-ferent way.” That really meant the world to me. That was what I was trying to explain to them! The people at the Kennedy Space Center have been just terrific. I’ve spent 13 weeks there since March of 1990. Some people ask, is NASA paying you to make the pictures? Well, I wish! It’s all my expense, which is fine. This is not a commercial assignment, it’s a personal assignment, and I’m not done yet. It was really hard to get per-mission and try and convince the people at NASA of what I was trying to do because they’re continually bombarded with photographers on assignment. They are all working on one aspect or another of the space program, and there are only so many people that NASA can accommo-date. I can’t offer anything but the nicest comments about the people at the Kennedy Space Center. TH: Are you still working on Places of Power? JS: No, Places of Power as a project is done. But I’ll continue to explore the magic and the mystery of the Anasazi sites. There are specific pictures in my mind I want to make at the Kennedy Space Center. My plan at the present, is in two years to do a book of all Space Shuttle photographs. It will include a number of pictures from Places of Power, but it will also include lots of additional images of the Shuttle and its realted support equipment. In the 22 or so Shuttle pictures in the book, I couldn’t show every-thing that I wanted to show. It’s a magic machine, and I’m anxious to get back to work on that project. I have lots of photographs I still want to make. TH: I’m curious about any photogra-phers whom you find inspiring or interesting, current or historical. JS: Certainly Ansel was a big influence. I have also been influenced by Wynn Bullock and the mystery that he conveyed in his photographs. I also love the graphic expression of Brett Weston’s photographs — they are photographs that still give me goose bumps when I see the orig-inal prints. I’ve got a Paul Caponigro print on the wall that I bought at a work-shop in 1974 for a hundred bucks, which was fifty bucks more than I had. I had to borrow fifty from my photography instructor. I’ve looked at that picture for 26 years and it’s still a magical image. I think Jerry Uelsmann’s photographs are very exciting. I really love Jerry’s work. I like the sense of humor in many of them, and the surrealistic quality, and I also have the highest respect for the pre-cision and the technical expertise in the way he combines images and makes it look so easy. TH: Do you have any other tips you could share with the readers — something you think might make their life easier in the darkroom? JS: I’ll start on the camera side of things, and then see if I can think of a darkroom tip. Now, I think this is really good advice. I always try to make two identical exposures, whether that’s with sheet film or roll film. Occasionally there are times when the picture just disappears, and there’s no sense exposing a second piece of film if the picture isn’t there, but so many times I’ve messed up a negative. I’ve accidentally scratched it, or dinged it going in and out of a negative carrier; or with sheet film I’ve had some sort of problem in processing. There are a few pic-tures I have gotten only because I had that second negative. In a general sense, I think it’s important to “listen to the materials.” And by that I am not trying to be metaphysical. To me, listening involves more than your ears — it involves being recep-tive. When I look at a print in the darkroom, I ask the question, is this achieving what I want? If not, what is missing? Then I try and take the necessary steps to reach that goal. I always try to take steps that are synchronized with what the photographic material wants to do. I try to think like film and I try to think like paper — and that sort of drives my decision-making process in terms of exposure and contrast, and dodging and burning when necessary. I’m not there to “argue” with the paper, I’m there to “converse” with the paper. And if we have a good conversation, we’re both go-ing to end up happy. I’m going to end up with the print I want, and the photographic paper is going to be happy to give that to me. That being said, sometimes what I want does not exist in the negative — and there’s nothing I can do in conversation to make that appear. So I have to buffer that with objec-tivity. That’s a little more general than a specific tip, but maybe that is something that might be helpful to your readers. |